When discussing what makes a great beef stew, the consensus is your beef chunks have to be moist and soft, not stringy, and the gravy has to be clear, flavorful and a rich brown. To achieve these goals there has to be a balance between the meat and the vegetables, all of which are suspended in a luxurious clear sauce. So how do you get perfect results every time? Let me explain…

Choosing the meat

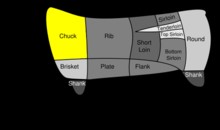

The first and the most important determining factor in what makes a great stew is choosing the best cut of meat for the purpose. As Julia Child wrote in her cook book Mastering the Art of French Cooking (1), “The better the meat, the better the stew” (p 314). Julia Child and many other well-known chiefs whose recipes I have read, state that they use either a Rump Roast (too lean for my purpose) or a Chuck Pot Roast (I prefer this cut because of the marbling). They suggest getting the entire roast and cutting it into large uniform 5 cm or 2 inch cubes. Cutting them all about the same size also helps because the meat will cook more evenly. Having irregular cubes in the stew with some chunks that are smaller, and will cook too fast, and ones that are larger, and will cook too slowly, results in an inconsistent texture to the stew meat.

Rump Roast

I do not use a Rump roast because I find it to be too lean and you have to cut it in thinner sections against the grain to get the best results. This does not work well for me.

Chuck Roast

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chuck_steak#/media/File:BeefCutChuck.png

I prefer using a Chuck Roast, also called Chuck Eye roast / Chuck Pot Roast / Chuck Roll Roast / Top blade roast from chuck (best cut) / Braising steak(UK) / Blade Roast (Canada). It is one of the classic cuts used to make a roast or stew.

https://www.certifiedangusbeef.com/cuts/Detail.aspx?ckey=101

The meat will be tender, moist and flavorful because of the balance of meat and fat, when it is cooked as described. Also, this is an economical cut of meat. It has a fair amount of collagen (which has health and nutritional value) which melts into the sauce when cooked slowly as in a stew.

Pre-cut stew meat

If you are buying pre-cut “stew meat” it should have “chuck” on the label. Otherwise it is probably some other cut such as from a round roast, which would not be as good for a stew. Also precut stew meat is usually cut into smaller cubes, 2.5 cm or 1 inch cubes or as I have found, they are usually cut into uneven cubes.

Remove the silver skin

As stated above, it is best to get the entire roast because you will see the quality of the meat and you can make sure that the cubes are large and uniform in size. If the roast has some silver skin on it, remove this thin surface layer before cutting into cubes. The silver skin will make the meat chewy because it does not break down during the cooking/roasting process.

To cut the roast, cut into even 5 cm or 2 inch steaks. Then cut the steaks into 5 cm or 2 inch cubes.

How do you get the best flavor from the meat?

Most of the meat’s flavor is a product of

- how it is cooked – browning

- the percentage of fat and marbling of the meat (think why Kobe beef is so prized)

- Flavor can also be obtained through brining (not for stews) or marinating (also not used for stews).

Cooking methodology explained

After cutting up the meat, using a paper towel, pat the cubed meat until it is completely dry. Making sure the meat is dry is very important in order to get a good sear. If the meat is damp or wet you will not be able to get the meat to have a good crisp sear/crust on the outside. The meat that has too much moisture will just steam or cook to an anemic brownish state.

How to sear/brown the meat

To get a good sear, (this applies to all meat, poultry and fish) pre-heat a dry pan over medium high heat until it is very hot and then add the oil. Add the cubes into the sizzling oil, making sure that the cubes are not crowded and there is plenty of room between the pieces. If you crowd the meat, it will steam and create a sauce-like liquid. This emitted liquid or sauce will prevent the meat from browning properly. Also if you add too many chunks of meat into the hot pan, it will lower the pan temperature too much, which affects the rapid browning of the meat needed for the Maillard reaction (see below) to occur properly. Therefore, it is better to brown the meat in smaller batches. Brown or sear until you have a good rich brown crispy crust on the bottom of each cube of meat. Check the bottom and then use tongs to rotate the cubes until all sides are browned. Since you are using a fairly high heat setting, this process should take one or two minutes per side. The purpose is NOT to cook the meat, but to just get a rich crispy brown exterior before you slow cook the meat in the remaining ingredients.

What does browning do to the meat?

The benefits of browning the meat were discovered by the French chemist Louise Camille Maillard in 1912. According to Harold McGee (2), a food scientist and author of On Food and Cooking, browning the meat develops the flavor in the stew. McGee also dispels the belief that browning the meat is done to “seal in the juices,” which he says is incorrect. What browning actually does is create a great deal of additional flavor through the “Maillard reaction.”

How does the Maillard reaction “create flavor”?

The Maillard reaction is a non-enzymatic reaction (an example of an enzymatic “browning” reaction, in contrast, is the browning of an apple or avocado after you cut it and the surface is exposed to air – the enzymes react and cause the surface to “brown”). The Maillard reaction is actually a chemical reaction that occurs between the amino acids (the building blocks of protein) and sugar molecules in the meat, when the meat is exposed to high temperatures between 149 – 260 C or 300 – 500 F, so the high heat acts as a catalyst (enables the reaction to occur) (3).

When you cook the meat at these high temperatures, the outside temperature of the meat is much higher than the inside of the meat and this temperature differential is what activates the Maillard reaction and results in all the great flavors on the surface of the meat. Scientists have identified approximately six hundred compounds resulting from the Maillard reaction, either directly or as a cascading series of subsequent reactions. The exact flavor combination is determined by the type of food being browned (4).

Other ways in which the Maillard reaction is used to color or flavor food:

- caramel made from milk and sugar

- the browning of bread into toast

- the color of beer, chocolate, coffee, and maple syrup

- self-tanning products

- the flavor of roast meat

- the color of dried or condensed milk

Example of the Maillard reaction, in more detail (5)

6-acetyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyridine is responsible for the biscuit or cracker-like odor present in baked goods like bread, popcorn, tortilla products. 2-acetyl-1-pyrroline flavors aromatic varieties of cooked rice. Both compounds have odor thresholds below 0.06 ng/L:

- The carbonyl group of the sugar reacts with the amino group of the amino acid, producing N-substituted glycosylamine and water

- The unstable glycosylamine undergoesAmadori rearrangement, forming ketosamines

- There are several ways for the ketosamines to react further:

- Produce 2 water andreductones

- Diacetyl, aspirin, pyruvaldehydeand other short-chain hydrolytic fission products can be formed

- Produce brown nitrogenous polymers andmelanoidins

Why “cook” the stew in the oven instead of the stovetop?

There is a very simple reason for cooking the stew in the oven, it cooks more evenly and at a constant and lower temperature because the heat is evenly distributed all around the pot. On the stovetop, the bottom gets hotter than the top so you get an uneven temperature in the pot.

One last thing, what pot to use for best results?

Use an oven proof 4 to 5 quart, wide and shallow pot. I use one of two types I own.

The first is an oven proof heavy bottomed stainless steel wide pot with a well- fitting lid that can go in the oven. See http://amzn.to/2qwQ8jz for this example.

The second pot I use is a French oven which is a cast iron pot that has a colorful enameled coating. It is like a Dutch oven but it is made in France – makes sense, n’est-ce pas? See http://amzn.to/2qwQ8jz for this example.

The Dutch oven is a bit heavier and can be used both on the stove and in the oven. See http://amzn.to/2rAeZqE for this example.

All of these pots can be used for moist cooking methods, like braising or making soups and stews, but can also be used for other cooking methods. An additional benefit from pots like these is that you can do all the steps in the one pot, from browning to sautéing vegetables, to cooking in the oven, to deglazing the fond and making the gravy. So much less mess and less clean up…

References

- Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Julia Child. Available at

http://amzn.to/2r7b9UQ - On Food and Cooking, McGee et al. Available at http://amzn.to/2rQjZHx

- https://www.exploratorium.edu/cooking/meat/INT-what-makes-flavor.html

- http://www.scienceofcooking.com/maillard_reaction.htm

- An Expeditious, High-Yielding Construction of the Food Aroma Compounds 6-Acetyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydropyridine and 2-Acetyl-1-pyrrolineTyler J. Harrison and Gregory R. Dake Org.Chem.; 2005; 70(26) pp 10872 – 10874; (Note) DOI: 10.1021/jo051940a At http://pubs.acs.org/doi/abs/10.1021/jo051940a?journalCode=joceah